Oscar was born over the weekend and as of today I’ll be blogging at growingsideways.wordpress.com. Looking forward to seeing you over there!

Author Archives: Kevin Hartnett

Marriage or children: Which is more important? Which should be?

As a recently minted husband and a new father, I’m interested in trends around marriage and childbearing. The 2010 Census has yielded a host of interesting patterns (detailed Census report here) in this regard: marriage rates are down for people of all demographics; marriage rates are down most dramatically among Americans with the lowest educational attainment (46% of Americans with a high school diploma or less are married, compared to 64% of college graduates who are married); Americans of all stripes are getting married later in life (the average age of marriage for men is 28, for women 26); successful marriages are increasingly concentrated among Americans with the most education (a college degree or more).

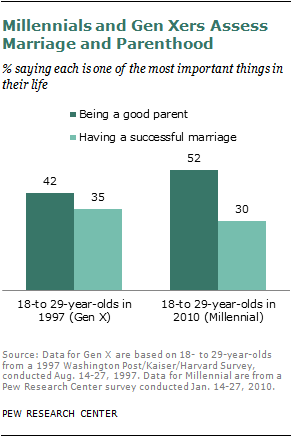

One of the most interesting pieces of analysis around marriage and childbearing trends comes from a survey by the Pew Research Center that found that members of the Millenial Generation (roughly speaking anyone born between 1980 and 2000) believe that being a good parent is more important in life than having a successful marriage: 52% of Millenials said being a good parent was one of the most important things in life while only 30% said the same thing about marriage. This roughly tracks with Census trends which show that Americans are getting married later in life and less often overall and also increasingly having children outside of marriage.

This result really struck me, first because in my own life I never considered having children before I’d gotten married, and second, because it’s unclear whether marriage or children is more important for happiness. My sense is that the available evidence suggests a successful marriage contributes more to happiness than children do. There’s the fact that married couples are better off financially than single people, and that marriage correlates with better physical health and longer life expectancy. At the same time there have been a slew of articles and studies in recent years questioning whether having children actually makes people happier, including this piece from New York magazine subtitled “Why parents hate parenting.” [N.b. It will come as no surprise that I disagree with the argument that children are detrimental to happiness; I’m just noting that it’s out there.]

It’s possible, then, that there’s a tension between what Millenials prioritize (children over marriage) and what will make them happy. At the same time, it’s also possible that Millenials have soberly concluded that while a happy marriage might not be possible for them, they don’t want that to mean they have to miss out on having children too.

Not ready for primetime: James at the tee ball game

Last Saturday morning James and I went down to Taney Park along the Schuylkill River. He insisted on walking to start but got tired halfway there and hopped aboard his tricycle. When we arrived the playground was nearly empty (I’m always surprised that dog owners are outside on weekend mornings far earlier than toddler owners) and James was bored. He had no interest in going down the slide; there were no kids whose toys he could try to steal; he picked up a pine cone and then dropped it. Then he saw a group of kids running around on a nearby baseball field and he perked up. “Yook kids,” he said, pointing. So we walked over to the chain link fence and watched the early innings of a tee ball game.

The kids were about six years-old though they looked like mini-Major Leaguers. They had on yellow and blue team shirts with the logo of a local business sponsor on the front and a number on the back. There were matching caps; most of the kids had on polyester baseball pants; a few even sported eyeblack.

Whenever I see kids even just a little older than James I can’t imagine how he’ll eventually turn into them. This has been true all along: It seemed impossible that he’d ever walk until one day he did; when he was born some friends gave him a Nike sweatsuit that was so big we stowed it at the bottom of a drawer thinking maybe he’d grow into it before he went to college. This spring I pulled it out, tags still affixed, and was shocked to discover that sometime, probably over the winter, his head had become too big to fit through the top of the shirt.

Kids of any age are a funny combination of skill and incompetence. When the tee ball sluggers stepped up to the tee they looked like pros: Their legs perfectly spaced, the bat cocked and wagging in their hands, their eyes bearing down on the pitcher who wasn’t actually there. Then they’d swing and reality was restored. Most of them hit the tee beneath the ball, which is one of the feeblest feelings in all of youth sports, for players and spectators alike. One of the dad/coaches would run quickly onto the field to replace the ball on the tee before the kid grew too discouraged. Everyone made contact eventually. Once you put the ball in player there was zero chance the fielders were going to get you out.

After a few batters James became more interested in the gravel along the bottom of the fence than the game, but I kept watching. I would have imagined a tee ball game as one big scrum but they actually did a good job holding their positions, just like the Phillies do.

I was curious about how they’d been assigned positions: Why was one kid directed to shortstop and another told to go play right field? On what basis was the kid with the knee-high stirrups made catcher? The assignments were probably fairly random but also consequential. In a couple years they’d be in Little League and the coach would ask them what positions they’d played before and the catcher would say catcher and the shortstop would say shortstop and the right fielder would kind of lie and say he didn’t really have a position. The process by which a child’s future possibilities winnow and branch goes on all the time; it just seemed particularly apparent to me that morning watching the baseball game.

Last fall James and I were in Rittenhouse Square when I started chatting with a dad who was there with his five-year-old son. The son had two baseball mitts and it happened that he wanted me to wear one of them. We played catch for awhile and I remember thinking “This is pretty fun. Won’t it be great when James and I can do this.”

But Saturday morning at the tee ball field I had the opposite feeling. For the kids I’m sure it was thrilling to step up to the tee and know that whether the ball flew or sunk was completely up to them; it seemed thrilling for the dads, too, who cheered and encouraged like it was Game 7 of the World Series. But for my part I was happy—for that day at least—to have James at my feet throwing gravel at the grass, and to know that in a short while he’d mount his tricycle and I’d push him home.

Parenting decisions today, a relationship with grown children tomorrow

There was an enjoyable essay in The Times this weekend about a mother taking a cross-country train trip with her two twenty-something sons. I agree with the observation the author, Dominique Browning, makes at the outset: “As parents, we are inundated with child-rearing books, but none of them explain how we should behave when children become adults.”

Over the course of the week-long trip from New York to San Francisco Browning distilled several lessons for how to have a good relationship with your children once they’ve grown up. They include:

- Don’t say everything that pops into your brain

- No more corrections of any sort

- Do interesting things together. Do anything together.

- Listen and do nothing. Or, do nothing and just listen.

- They will never be 8 years old again. Nor do you want them to be. Not really. Just a bit.

James’ turned two just last week, so it’s not quite time to worry about how I’ll handle things the first time we have a beer together. In her essay Browning says that one of the keys to the success of the trip was that she let her twenty-six-year-old son Alex plan the itinerary as a way to show that she considered him an adult. This morning I let James plan the walk to daycare and it was a disaster. It took 20 minutes to walk two blocks and the experiment ended with him screaming in my arms, “I wanna touch it,” as I hauled him away from a pile of dog poop.

Even though we’re a few years away from traveling together as equals, I still think about how the relationship James and I have now will translate once he’s an adult. The first two years of his life have passed in what feels like almost not time at all; I imagine the next 16 will, too. Given that James will have no choice but about spending time with for only a relatively small percentage of the years we have together, I want to make sure that the relationship we form while he’s young sets the stage for the relationship I hope we’ll have when he’s older.

I don’t have any particularly keen insights for how to accomplish that. As parents we probably have less to do with that process than I think. (Maybe one-third of a child’s eventual happiness owes to his parents, with the rest just alchemy?) But in the day-in-day-out sometimes slog of parenting I find that thinking about the relationship I’ll have with James when he’s older is a useful way to remind myself of a larger point: that Caroline and I are raising a child whose life is ultimately his own.

Disciplining a toddler with timeout: smart or soft?

Almost nothing stays with a kid longer than the feeling of being punished by his parents. What I remember most is not the particulars of the punishment—a spanking, a bar of soap, not being able to drive for a month—but the feeling of having done wrong in my parents’ eyes. Even at 30 it would still hit me hard if my dad were to let me know that he thought I’d acted badly.

I had this thought in mind yesterday at lunchtime when James launched his sippy cup into the tray of the open dishwasher. It clattered among the dirty plates and startled me enough that I dropped/slammed the wooden cutting board I was washing down in the sink. “That was not funny,” I shouted as I spun his high-chair around to face away from the kitchen. “You’ve got timeout!”

Now, I didn’t receive timeout as a kid but Caroline and I have taken to using it as parents. I think of it as one of the stereotypical practices of middle class American childrearing. I’ve read several academic studies about parenting recently and in the compare and contrast between American-style parenting and parenting styles in other parts of the world, “time out” is always listed as a key distinction between the way we raise our children and the way the Kalahari bushmen raise theirs. If it’s not on Stuff White People Like it should be.

I asked Caroline why she thinks “timeout” is ridiculed. “Because it’s wussy,” she said. That sounds right to me. The most obvious point of comparison is the belt, as in “Dad’s going to get the belt if you don’t shape up,” and in that sense timeout is just another way that late-stage American culture has grown soft. During the ’08 presidential campaign Hillary Clinton called Barack Obama a Pollyanna after he said he’d be willing to hold diplomatic talks with the world’s worst dictators. In her view dictators, like toddlers, only respond to force. (Caroline adds that it’s misguided to think that either dictators or toddlers respond to force or to diplomacy: “They’re both just crazy,” she says.)

So I felt like a bit of a caricature yesterday as I gave James timeout for throwing his cup in the dishwasher. When his minute was up I turned his seat back around and asked him if he knew why he’d been given timeout. “No throw cup a dishwasher,” he said.

“That’s right,” I replied, pleased to hear that the time he’d had to contemplate his misdeed had clarified things for him. “We don’t throw the cup in the dishwasher.” The grin on his face told me that he was already plotting his next projectile.

One of the central things timeout accomplishes is that it depersonalizes punishment. If James throws his cup into the dishwasher and is given timeout, the implication is that he did wrong by the dishwasher. If, instead, James throws his cup into the dishwasher and dad flies into apoplexy, the implication is that he did wrong by dad. The difference between timeout and spanking is like the difference between a police officer giving out a parking ticket—”Nothing personal, I’m just doing my job”—and God raining fire and brimstone on Gomorrah—”You better believe it’s personal.”

So which approach is better? I’m not a timeout kind of parent by disposition but I’ve warmed to its merits. I like that with minor events like the dishwasher incident timeout keeps the interaction between me and James simple and more predictable. As he gets older and the lessons he learns grow more complex I hope I’ll keep in mind how powerful my parents’ judgments were to me as a kid (both when they’d praise me and when they were angry at me), and be conservative in how and when I express my own judgments to James.

At the same time, I know that I’m going to be an integral part of James’ moral world as he grows up, and that my responsibility to him is as more than an umpire who dispassionately calls strikes and balls in his behavior.

A family walk in the city

It’s rare that Caroline and I run errands together in the city. Usually when one of us goes out (and brings James along) it’s an occasion for the other to get some work done. But on Friday afternoon we were all eager to get out of the house so we set off together get ingredients for dinner that night: a cold pasta salad with shrimp, feta, olives and dill.

James resisted getting in his stroller, as he often does, and rather than cajole him we let him walk alongside us. He took my index finger in his hand and with Caroline pushing the empty stroller beside us we walked slowly down the block. At the first intersection the cross light was just turning yellow. Normally I would have zipped across at the last second, but that’s hard to do with James at my side. So we waited a minute and watched the cars go by. “Yellloow taxi cab,” James said excitedly as one and then another sped by.

There are all sorts of stories about the merits of going slow. One of my favorites is Shel Silverstein’s The Missing Piece. It’s a simply illustrated book. The main character is a circle with a dot for an eye and a pie-slice mouth. He rolls along looking for his missing piece and as he goes he sings a happy song:

Oh I’m lookin’ for my missin’ piece

I’m looking for my missin’ piece

Hi-dee-hi, here I go

Lookin’ for my missin’ piece

The book is a series of minor adventures. He bumps into a stone wall, bakes in the sun, cools in the rain. The land is littered with pie-shaped pieces but none turn out to be his missing piece: one is too sharp, another is too small, one is too square, another is too surly and rejects him.

Finally the circle comes across a piece that looks just right. Their initial exchange still breaks my heart:

“Hi,” it said.

“Hi,” said the piece.

“Are you anybody else’s missing piece?”

“Not that I know of.”

“Well, maybe you want to be your own piece?”

“I can be someone’s and still be my own.”

“Well, maybe you don’t want to be mine.”

“Maybe I do.”

“Maybe we won’t fit…”

“Well…”

And they do fit. And because the circle is now complete he rolls along faster than ever before, so fast that he can’t stop to talk to his old friend the beetle or say hi to a butterfly. Worst of all, the addition of the new piece means that when he tries to sing, the words come out garbled because his mouth is now full of piece.

This leads to an epiphany. “‘Aha,'” it thought. “‘So that’s how it is!'” The circle places the new piece gently back down on the ground and then rolls on, slowly, without it, still singing his song. The simple idea conveyed by the book—that the things we want most are the things we cannot have—has stayed with me more powerfully than just about any story I’ve ever read.

The walk to the grocery store took twenty minutes, about twice as long as it usually does. Once inside James tried to knock over a tower of canned tomatoes, so I picked him up. Caroline got a cube of feta at the cheese counter and a carton of grape tomatoes. James watched her as she began to scoop oily kalamatas from a barrel into a shallow plastic container. “I wanna watch, I wanna watch,” he said in an urgent voice, straining to look over my shoulder to get a better look at what Caroline was doing. It occurred to me that if you’d never seen a barrel of olives before, as he hadn’t, then for a moment it might appear to be the most interesting thing in the world.

Everyday James sees a multitude of things which, for a moment at least, probably count as the most interesting thing he’s ever seen. Adults might go years without seeing anything that stirs us to wonder half as much as those olives stirred James. A recent New Yorker profile of a Baylor University neuroscientist explained how our increasing familiarity with the world relates to the fact that time seems to move faster as we grow older: “The more detailed the memory, the longer the moment seems to last…The more familiar the world becomes, the less information your brain writes down, and the more quickly time seems to pass.”

That sounds right to me. I remember a few years ago it was late-November before I’d noticed that the leaves had begun to fall from the oak tree outside my apartment. By that time the tree was nearly bare and I found myself thinking, “My God, I can’t believe it’s already Thanksgiving again.”

I don’t know the British Romantic poets from Adam, but recently I did stumble across a poem by William Wordsworth called “Ode on Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood.” It’s about how wonder fades as we grow older. The first stanza:

There was a time when meadow, grove, and stream,

The earth, and every common sight

To me did seem

Apparelled in celestial light,

The glory and the freshness of a dream.

It is not now as it hath been of yore;–

Turn wheresoe’er I may,

By night or day,

The things which I have seen I now can see no more.

Maybe there is no getting back the wonder of childhood, but after we’d finished our grocery shopping and returned home, it occurred to me that having a child helps. When I’m by myself I try to get where I’m going as fast as I can and I pay attention to just what’s necessary to carry out the task in front of me, but walking with James changes my pace and my perspective. At the same time, I wouldn’t want to inhabit James’ world all the time; I like being able to separate the wheat of experience from the chaff, and to use the room such sorting creates to think about, among other things, how different his world is from mine.

The amazing lives of bees

This morning my review of The Beekeeper’s Lament by Hannah Nordhaus runs in the Christian Science Monitor. It’s a very good book. Nordhaus spent a couple years with a migratory beekeeper named John Miller as he trucked his half-a-billion bees around the country and rented them out for weeks at a time to pollinate almond orchards, orange groves, and clover fields, etc. (As a result of monocultural crop planting local bee populations are rarely big enough to keep pace with agribusiness pollination needs.)

The best part of the book for me was learning more about bees. My prior knowledge was so limited that I hadn’t even put it together that “Clover Honey” means honey that was produced by bees who got their succor pollinating fields of clover. There are, as it turns out, nearly as many varietals of honey as there are types of flowers. Among them one of the most noxious and inedible is said to be honey produced from onion blossoms.

As I was reading The Beekeeper’s Lament I shared bee trivia with just about everyone I ran into. A couple of my favorite bee-related factoids made it into the review (including a quick recap of the astonishing one-and-only flight the queen bee makes outside the hive in her life). Here are a few that did not:

- It takes 80,000 bees working all summer and visiting 2 million flowers to produce a single pound of honey

- The average honeybee produces one-twelfth of a teaspoon of honey over the course of his six-week lifetime

- Migratory bees pollinate $15 billion of crops every year, and make possible 1 in every 3 bites of food from each summer’s harvest. Given the importance of migratory beekeeping to food production, I was particularly surprised that pollinators-for-hire only became a big business in the late-1990s.

- In 2002 the FDA banned all honey imports from China after Chinese beekeepers used a nasty pesticide to combat an outbreak of a bacterial disease called foulbrood. The ban didn’t work, though. The Chinese started routing all their honey through third-party countries like Vietnam and Australia. Honey from China is still illegal to import into the US, but Nordhaus writes, “Suppliers suspect that 50 percent or more of all imported honey has been transhipped from China through another country.”

- Every January two-thirds of the nation’s bees are trucked to the Central Valley in California to pollinate almond trees.

Overheard: a conversation between a mom and her son

On Sunday night while I was waiting at the corner of 34th and 8th Avenue in Manhattan for the bus to Philadelphia I overheard a conversation between a mother and her son that reminded me of conversations I used to have with my mom.

The son was in college and had just finished for the summer. He had a thick beard and was dressed in blue jeans and a long-sleeve athletic shirt. The mom was in her late-forties, short, and neatly put together. She didn’t look young, but she didn’t yet show any signs of middle age.

The mom asked her son one question after another, mostly about his friends. “How’s so and so doing,” she’d say. Or she’d give him an update on some family friend. “Did you know that Jess Kasenbaum is going to medical school?”

The son’s answers were short and generic. “He’s doing fine,” or “Same as always,” or, “Oh, good for Jess.” The whole time he fiddled with his smart phone. In most conversations his responses would have been taken as a sign that he didn’t really want to talk. But the mom either didn’t get the hint or she chose to ignore it, and the son seemed content to go on giving half-answers.

The second aspect of their conversation that struck me was the son’s disposition: He acted like he knew a lot more than his mom did. At one point while we waited a homeless man walked the bus line handing out copies of The Onion that he’d unpacked from the newspaper box around the corner. The son said he’d already read that issue but he took a copy for his mom and, after a minute of digging in his backpack, handed the man what looked to be about 30 cents. “You’ll like this, it’s really funny,” he said to his mom, in the same tone that a parent might use to cajole his kid into eating vegetables: “Eat these, they’re good for you.”

I remembered feeling that same flush of cultural superiority towards my mom whenever I introduced her to new music, or explained what instant messaging was, or helped her read the NYC subway map.

The two of them talked about more serious topics, too. From what I could tell there’d been a divorce recently. “Your father wasn’t a good husband to me,” I overheard the mom saying. “He’d always walk two blocks ahead of me when we were in the city.”

This son looked up from his phone and said something I couldn’t quite make out. The mom spoke more loudly, less self-consciously than he did. I could hear her clearly when she said, “I miss the unity of being a family, that’s what I miss. But I don’t miss him at all, not for a minute.”

The son gave his mom some advice: “I hear people talking like this all the time, complaining about their problems instead of doing something about it.” It wasn’t the most generous thing he could have said but I had some sympathy for the son; it’s hard to know what to say when your parents bare themselves to you like that. As a kid you want to be able to say to your parents what they always said to you: everything’s going to be all right. It’s a lot harder to accept that some people live unhappy lives and that your parents might be among them.

Eventually the bus arrived. The mother and son boarded before I did and I didn’t see where they sat down. We drove south on the Jersey Turnpike; the glow of streetlamps raced through the interior of the bus. As I continued to think about the conversation I’d overheard I was surprised to find myself identifying more closely with the mother.

The son may have known many things his mom did not. He knew about The Onion. He told his mom to “calm down” when she started worrying about the bus being late. He had advice for how to deal with a divorce. But when it came to the single most important thing between them—how much she loved him—it seemed to me that the mother knew it completely and the son had no clue.

Reconnecting with children’s books as an adult

I’ve got a short essay up this morning about the experience of reconnecting with children’s books I loved as a kid now that I’m reading them to my son:

The books that parents read to their very young children don’t change much from generation to generation. When my son was born two years ago I was surprised to find that with few exceptions, the titles we welcomed into our Philadelphia apartment were the same ones that three decades earlier had served as my own introduction to storytelling.

I made an informal study of the Amazon sales rankings of the books I enjoyed having read to me most as a kid. It seemed to confirm that taste in books for young children is remarkably constant. Here are just a handful of popular titles with their publication years and their overall Amazon ranks…

Kenyon Grads Reflect on DFW’s 2005 Commencement Speech

Time Magazine calls David Foster Wallace’s 2005 speech to the graduates of Kenyon College the best commencement speech ever given. I’ve been a fan since a friend emailed it to me a few years ago and since then I’ve returned to it a couple times a year and shared it with lots of friends. Recently I began to wonder: What did the speech seem like to the graduates who heard it live? To answer that question I interviewed graduates of the Kenyon Class of ’05. I have an essay out this morning describing what I found.

On May 21, 2005 David Foster Wallace delivered the commencement address at Kenyon College. In the years since, the speech has come to play an important role in way Wallace’s work is received and remembered. Depending on who you ask, the speech is the clearest distillation Wallace ever gave of the themes that run through his fiction, or it is a powerful practical guide for how to live a good life, or—in the way the speech has been marketed since—it’s an example of how a vibrant, challenging artist can be packaged for mainstream consumption.